April is National Poetry Month, and there’s no better way to celebrate than by reading and learning about poetry! Last year, we developed a guide for learning figurative language through poetry, since metaphorical and abstract language thrives in the work of poets. Another important aspect of poetry is rhyme scheme, which helps writers develop rhythm and tone. Because understanding how to identify rhyme schemes and their purpose is a key ELA topic, we’ve developed this guide to finding rhymes and a collection of poems to teach rhyme scheme in hopes of aiding students in learning this important skill!

How to Find Rhyme Scheme in Poetry

A rhyme is created with sounds that repeat at the end of lines or phrases, and a rhyme scheme is a pattern of rhymes throughout a piece of writing. Rhyme is typically used to add rhythm and tone to a spoken-word work of writing, and it has been used for centuries in songs, chants, plays, poetry, and children’s stories. The easiest way to identify a rhyme scheme in anything is by reading it aloud!

Let’s use a famous nursery rhyme as an example:

“Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall, Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men Couldn’t put Humpty together again.”

“Wall” and “fall” are rhyming words, so those two lines create a rhyme. “Men” and “again” also form a rhyme. Together, the two rhymes develop the rhyme scheme of “Humpty Dumpty”: AABB.

People describe rhyme schemes by assigning a letter of the alphabet to each unique sound at the end of a line or sentence. You keep track of the rhymes used in a poem by assigning “A” to the sound at the end of the first line, “B” to the next different sound, “C” to the third different end-of-line sound, and so on. When a sound is repeated, forming a rhyme, you repeat the letter assigned to that sound.

For example, ABAB means that the first and third lines in a stanza rhyme, and the second and fourth lines rhyme. ABCB means that the first and third lines don’t have a rhyme, while the second and fourth rhyme with one another.

Identifying Rhyme Scheme: Eye Rhymes and Near Rhymes

Finding rhyming schemes in poetry, plays, and songs can be easy, since you can often visually spot rhymes based on the similar spelling of two words (like “wall” and “fall”). Still, there are many exceptions.

Eye Rhymes: Looks Can Be Deceiving

Not all words that are spelled similarly rhyme. For example, “bear” and “fear” share an identical spelling after the first letter, but they are pronounced differently and don’t actually rhyme. These types of word pairs that “look” like they rhyme but actually don’t are eye rhymes/sight rhymes.

At the same time, there are many rhyming words that are spelled quite differently. “Men” and “again” (like in “Humpty Dumpty”) have very different spellings, but they form a rhyme. “Flair” and “bare” is another example.

Languages evolve and change over time, often resulting in the pronunciation of certain words changing. Many lines from older English poems used to rhyme but no longer do because of the evolution of the English language—these result in a type of eye rhyme called a historic rhyme. Consider this example from Shakespeare’s Hamlet:

“The great man down, you mark his favourite flies;

The poor advanced makes friends of enemies.”

These lines follow an AA rhyme scheme, but the pair “flies” and “enemies” does not rhyme in today’s English. When Shakespeare wrote Hamlet around 1600, the two words rhymed in local dialects—it was a true rhyme that became an eye rhyme over time.

Near Rhymes: Close Enough!

In rhyming poetry and songs, you’ll often come across near rhymes/approximate rhymes—words that sound very similar but aren’t perfect rhymes. Some examples of near rhymes are “sauce” and “cost”, “orange” and “door hinge”, or “pecked” and “select”. Songwriters and poets often use near rhymes to get a particular idea across in cases where a true rhyme doesn’t exist.

“How Do I Love Thee?”, a sonnet by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, shows an example of near rhyme in poetry:

“How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal of Grace.”

To make the ABBA rhyme scheme work, Browning develops an approximate rhyme of “ways” and “Grace”—the words don’t end with the same exact sound, but they’re close enough!

Common Rhyme Schemes in Poetry

While rhyming poems don’t have to follow a specific pattern, there are many common types of rhyming formats that writers use in their rhythmic work.

Simple Quatrain Rhyme Schemes

These rhyme scheme examples are the most common varieties you’ll see in poems and songs with four-line stanzas (also known as quatrains). Writers using this rhyme scheme can maintain the same rhymes throughout (Ex. ABAB ABAB…) or change the rhymes in each stanza (Ex. ABAB CDCD…), which is the more common approach.

1. Alternate Rhyme: ABAB

Alternate rhymes simply alternate a rhyme throughout—in each stanza, the first and third lines rhyme and the second and fourth lines rhyme.

“Far or forgot to me is near;

Shadow and sunlight are the same;

The vanished gods to me appear;

And one to me are shame and fame.”

(Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Brahma”)

2. Enclosed Rhyme: ABBA

In an enclosed rhyme stanza, the first and fourth lines rhyme and the second and third lines rhyme. Also referred to as an internal rhyme scheme, the A rhyme “sandwiches” the B rhyme in this format.

3. Simple Four-Line Rhyme: ABCB

A straightforward rhyme scheme in which only the second and fourth lines of a stanza rhyme, the simple four-line rhyme scheme is also called a ballad stanza. Poems using this rhyme scheme typically continue the pattern throughout, sometimes using repetition instead of rhyme.

“Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.”

(Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”)

4. Monorhyme: AAAA

If you’re familiar with the Greek prefix “mono” meaning “one”, you understand that a monorhyme is a rhyme scheme in which the same rhyme is repeated. Writers can use the same rhyme throughout a stanza and switch to a different rhyme sound for the next stanza (Ex. AAAA, BBBB…), or they can continue the same rhyme sound throughout the whole piece.

Note: A monorhyme formatted into different two-line stanzas is called a rhyming couplet: AA, BB, CC, DD. Rhyming couplets (or “coupled rhymes”) can make up an entire poem, or they can be integrated into a poem alongside a different rhyme scheme.

Fixed Verse Rhyme Schemes

Poems with rhyme schemes can follow more complex patterns of rhymes instead of repeating a four-line rhyme scheme like the ones above. These longer rhyme schemes are designated formats that poets have utilized in their work for hundreds of years.

1. Ballade

The ballade is generally made up of three eight-line stanzas that follow an ABABBCBC rhyme scheme before a final, four-line stanza with a BCBC rhyme scheme. It is often used to convey a very formal, solemn tone.

Note: Don’t confuse the ballade with the ballad, which is a very long narrative poem made up of many four-line stanzas (which are usually the simple four-line rhyme—ABCB).

2. Sonnet

The sonnet is a widely-used 14-line form of poetry with distinct variants. The Petrarchan sonnet is three stanzas, the first two of which follow an identical enclosed rhyme scheme (ABBA ABBA CDECDE/CDCDCD), while the Shakespearean (or “English”) sonnet is composed of three quatrains and one couplet that functions as a twist (ABAB CDCD EFEF GG).

3. Villanelle

Also known as a villanesque, the villanelle is made up of nineteen lines—five tercets (three-line stanzas) followed by a quatrain. This form of poetry has a rigid rhyme scheme: each tercet follows an ABA rhyme scheme, while the quatrain follows the pattern ABAA. The villanelle also involves refrains—the first line of the poem must also be the sixth, twelfth, and eighteenth lines, while the third line of the poem must repeat for the ninth, fifteenth, and nineteenth lines.

4. Limerick

A tone shift from the more serious styles above, a limerick is a form of poetry popular in children’s rhymes and stories. While it also has rules when it comes to meter (the syllabic structure of a line) and internal rhyme (rhyme within a single line of poetry, rather than only at the end of a line), its simpler rhyme scheme combines the rhyming couplet with an enclosed rhyme: AABBA.

Eight Poems to Teach Rhyme Scheme

Now that you’re equipped with a baseline understanding of how to find rhyming scheme and some of the different formats used in rhyming poetry, let’s dive into some amazing poems to teach rhyme scheme.

From lesser-known works of acclaimed poets to famous poems known around the world, these works are fantastic tools to practice finding rhyme schemes, identifying common fixed verse rhyme schemes, and even analyzing the effect that rhyme has on a poem’s meaning and tone.

“Auguries of Innocence” by William Blake

Considered a nonconformist and visionary of the English Romanticism movement, William Blake (1757–1827) wrote about a wide range of topics including political criticism, the strength of the human spirit, spirituality, and nature. In “Auguries of Innocence”, Blake grapples with the good and evil present in everyday life, drawing attention to symbols of purity and innocence by contrasting them against negative, more malicious or “sinful” ideas.

This poem is not split into stanzas, as it is one long “paragraph” of consecutive lines. The rhyme scheme shifts from one pattern to another towards the beginning, and while the bulk of the poem seems like rhyming couplets, keeping track of all the rhymes may reveal that Blake involved a more consistent approach than you may think at first glance.

“The Catterpiller on the Leaf

Repeats to thee thy Mothers grief

Kill not the Moth nor Butterfly

For the Last Judgment draweth nigh”

(Lines 37–40)

“Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” by Dylan Thomas

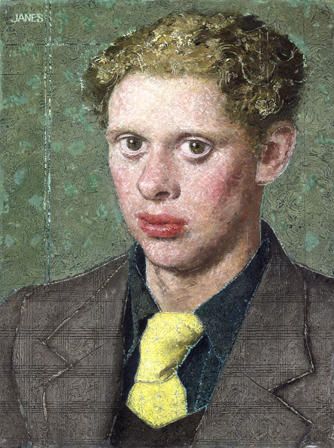

1934 painting of Dylan Thomas by Alfred Janes.

Dylan Thomas (1914–1953) is another exceptionally original poet, known for his innovative lyricism and imagery. While he didn’t align with any one group or movement of modern poetry, his work drew upon ideas from the romantic movement, surrealism, and even folklore. Often, it focused on topics like unity within diversity and the cyclical nature of life.

“Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” is a famous modern villanelle about how one should fight for life even when death is impending and inevitable. Referenced and recited in dozens of modern novels and films, analyzing the fixed verse together with its subject matter and figurative language can reveal how Thomas achieved the emotional depth in this poem.

“Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

(Lines 1-3)

“Banking Coal” by Jean Toomer

The poetry of Jean Toomer (1894–1967) lyricizes the early 20th century experience of Black Americans and champions racial unity with an inspirational, uplifting tone. Though he is commonly associated with the Harlem Renaissance and the modernist movement, he rejected all such associations—as a mixed individual, he also resisted being labeled as “Black” or “white”.

“Banking Coal” speaks to the power of a single individual—how one person taking action can spark a massive change. It belongs in this collection of poems to teach rhyme scheme because of the way Toomer involves alternate rhymes and rhyming couplets at different points, developing a unique rhyme scheme that doesn’t fit neatly into one pattern. As you read, consider the detailed imagery together with the repeated rhymes and words throughout the poem.

“Whoever it was who brought the first wood and coal

To start the Fire, did his part well;

Not all wood takes to fire from a match,

Nor coal from wood before it’s burned to charcoal.”

(Lines 1–4)

“The Soul has Bandaged moments- (360)” by Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson, 1846/1847.

Emily Dickenson (1830–1886) is one of the most celebrated American poets of all time. Looking through her vast collection of poetry reveals that she had a particular penchant for rhyming—most, if not all, of her works rhyme, so she is a must-read when it comes to learning about rhyme schemes.

“The Soul has Bandaged moments” is not very different from her other poems, both in terms of its subject matter and its rhyming structure. Dickinson frequently wrote about topics like death, immortality, and the human soul (the focus of this poem), most of her poetry includes an alternate rhyme scheme, and she was never afraid of using near rhymes on her quest to get her ideas across. Looking into the rhyme scheme of this poem in particular shows a shift away from the expected pattern. Those who take a closer look can see the internal rhymes Dickinson imbues into the poem (pay attention to “Bomb” and “opon” in the last two lines).

“The soul has moments of escape –

When bursting all the doors –

She dances like a Bomb, abroad,

And swings opon the Hours,”

(Lines 11-14)

“Tamerlane” by Edgar Allan Poe

Known for his spooky stories and emotional poems, Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849) had a massive impact on American literature. His tales (like “The Raven”) are regarded as the vanguard of detective stories and horror fiction. Throughout his work, he’s known for masterfully using both rhetorical devices and rich figurative language to develop a frightening ambiance.

“Tamerlane” is about the relationship between independence and grief in a person—Poe writes from a fictionalized perspective of Timur, the conqueror that founded the Timurid Empire in the 14th century in Central Asia. For this speech to the speaker’s father, Poe weaves an intricate web of rhyme that follows no established fixed verse. Think: how do the rhymes help Poe convey the particular tone he is developing?

“Know thou the secret of a spirit

Bow’d from its wild pride into shame.

O! yearning heart! I did inherit

Thy withering portion with the fame,

The searing glory which hath shone

Amid the jewels of my throne,

Halo of Hell! and with a pain…”

(Lines 13-19)

“The Wild Swans at Coole” by William Butler Yeats

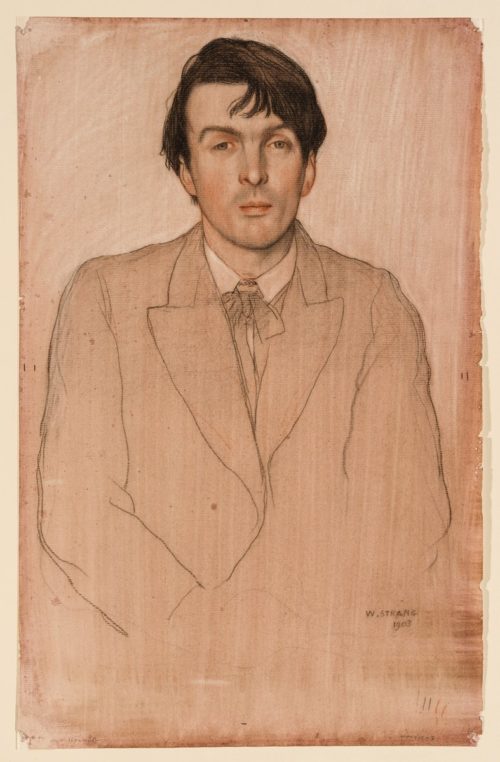

1903 drawing of William Butler Yeats by William Strang.

Irish poet William Butler Yeats (1856–1939) was a powerful force in 20th-century literature—as a Symbolist poet, he frequently used symbolic imagery and structures throughout his poetry. Although he is often remembered as one of the first Modernist poets, his early poetry is full of more traditional, Romantic forms, including rhyme schemes.

“The Wild Swans at Coole” is a magnificent nature poem about the tranquility of an Autumn lakeside scene. In it, Yeats uses precise imagery to paint a landscape of a lake in which fifty-nine swans are drifting. This combined with the unique rhyme scheme grants the poem an emotional tone that touches the reader’s heart.

“The trees are in their autumn beauty,

The woodland paths are dry,

Under the October twilight the water

Mirrors a still sky;”

(Lines 1-4)

“Phenomenal Woman” by Maya Angelou

An unparalleled poet, novelist, and civil rights activist, Maya Angelou (1928–2014) has received dozens of awards for her writing. Her poetry is understudied by literary critics (especially in comparison to her prose), but it’s widely popular—she’s been described as “the black woman’s poet laureate”, demonstrating how her poetry speaks to everyday people.

A ballad of female self-empowerment, “Phenomenal Woman” is one of Angelou’s most popular poems. She crafts an argument that embracing one’s uniqueness, especially as a Black woman, inspires the growth of powerful self-confidence. Angelou develops these strong ideas through the use of repetition and figurative language, but her implementation of rhyme takes it to the next level. Students should consider the rhyme scheme she chose and how it complements the structure of the poem as a whole.

“It’s in the reach of my arms,

The span of my hips,

The stride of my step,

The curl of my lips.

I’m a woman

Phenomenally.”

(Lines 5-11)

“The Runaway” by Robert Frost

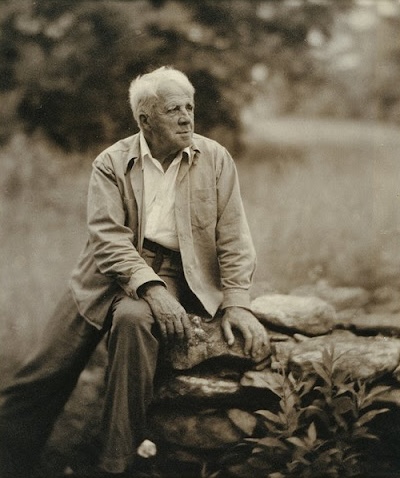

1955 photograph of Robert Frost by Clara Sipprell.

Robert Frost (1874–1963) was known for writing rhyming poetry that realistically depicted life in rural New England. He symbolically utilized nature poetry to convey themes of life and society, combining colloquial speech with traditional poetic forms. You may know him for “The Road Not Taken”, a poem about diverging paths in life symbolized by a fork in a forest road.

Similarly, “The Runaway” uses natural themes to convey Frost’s ideas about life and humanity. The poem is a short story about finding a frightened and lost young horse by a mountain pasture in winter. This tale conveys the innocence that all young living beings have, whether they are human children or young animals. Frost’s rhyme scheme swaps between dual rhymes and alternate rhymes—keep track of the rhymes and think about why he decided to shift the sounds when he did.

“‘I think the little fellow’s afraid of the snow.

He isn’t winter-broken. It isn’t play

With the little fellow at all. He’s running away.”

(Lines 9-11)

Improve Reading and Writing Skills with Piqosity

We hope this collection of poems to teach rhyme scheme was both informative and entertaining! Celebrating national poetry month by reading and learning about rhyme is a wonderful way to exercise ELA skills while enjoying the rhythm and songlike quality of poems.

If you’re struggling with concepts like figurative language or looking for ways to improve your English skills, Piqosity’s here to help! Along with our Digital SAT and ACT test prep courses, we also offer full online English courses—each includes dozens of concept lessons, personalized practice software, and over 100 reading comprehension passages.

- 5th Grade English Course

- 6th Grade English Course

- 7th Grade English Course

- 8th Grade English Course

- 9th Grade English Course

- 10th Grade English Course (new!)

- 11th Grade English Course

The best part? Try out all of Piqosity’s features with our free community account, which feature a free mini diagnostic exam to evaluate your current ELA skills. When you’re ready to upgrade, Piqosity’s year-long accounts start at only $89. Plus, get a 10% off coupon just by signing up for our mailing list!

Leave A Comment